In the A to Z of Becoming, D can stand for Dream. Let’s consider three different kinds of active dreaming this week.

Probably when you first think of dreaming, you think of the dreaming you do when you are asleep. Dream experiences are astonishingly diverse. From almost mundane rehearsing a day’s events, to bizarre, symbolic totally baffling dreams, to dreams which feel important somehow. And how annoyingly common it is for the dreams to vanish in a flash as you wake leaving you with some kind of memory of having been dreaming, but the content has suddenly become inaccessible. Lucid dreams are ones where the dreamer is aware of dreaming. It doesn’t happen often for me, but when it does the dream always has the feel of significance. My most recent lucid dream was like that. As I flew above the Earth I was aware I was dreaming and that this experience was potentially important to me so chose to zoom down and look carefully to see what I could see. What I saw astonished me and is working its way out in my life in a myriad of incredible ways. (Maybe I’ll describe it some time for you)

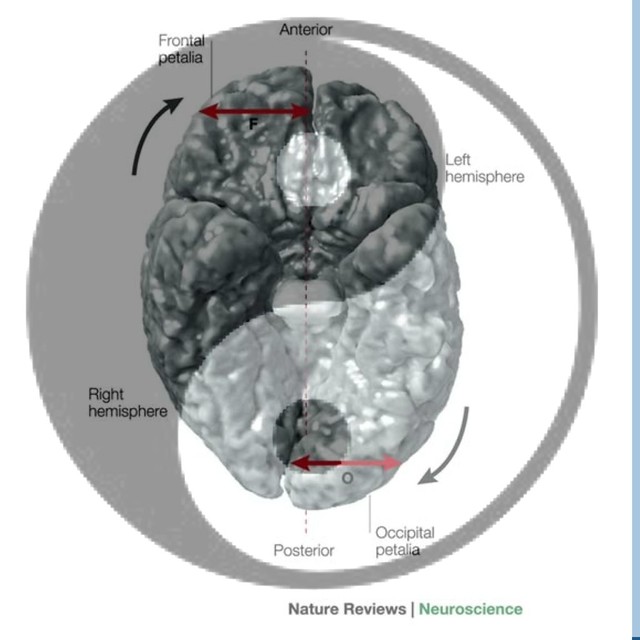

Scientists have discovered something very interesting about lucid dreams. The part of the brain which seems active during self-reflection is especially well developed in lucid dreamers, raising this interesting prospect –

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin and the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry in Munich have discovered that the brain area which enables self-reflection is larger in lucid dreamers. Thus, lucid dreamers are possibly also more self-reflecting when being awake.

This is one of those fascinating chicken and egg scenarios. If you could train people to experience lucid dreaming more frequently, would that assist them in becoming more self-reflective? And the other way too…..if you practice more self-reflection, do you have more lucid dreams?

So, there’s the first type of active dream to consider – lucid dreaming. If you have a lucid dream stick with it. My experience suggests that it will pay off in abundance. If you don’t have lucid dreams, developing daily self-reflective practices such as journaling, or meditation, might increase your chances of having one. (And you will probably receive the benefits of the self-reflective practices anyway)

A second kind of active dream is the conscious, heading towards something kind of dream. I find it is very common to discover that top musicians, artists, or sportsmen and women, dreamed of their achievements even as children. If you have such a dream, if you desire with all your heart to develop a particular skill or talent, then that dream may well contribute to its coming true. Whilst we can’t all be top performers in some area, I do think that the consistent dreams which run over many years generate both motivation and commitment. I dreamed of being a doctor when I was three years old, and I can’t remember a time throughout my whole childhood that I didn’t have that dream. Once I became a doctor, the dream modified to become more specific. I dreamed of being a particular kind of doctor. By that, I mean a doctor who practiced according to certain values. That dream underpinned all my career choices. I’ve also had a dream since childhood to become a writer, and that’s something I’m realising more consistently now, than at any previous stage of my life.

What dreams do you have for you life? What does your heart desire? What does your soul long for? If you know, why not take some time to write it out. Describe it, make it more concrete, lay the foundations for the life you hope for. If you don’t know, you could start to journal about it, or to meditate about it, or to discuss it with a loved one. Explore potential dreams and see what makes your heart sing. (By the way, that constitutes self-reflection, so such a practice might increase your chances of lucid dreaming)

Finally, a third kind of dream is a day dream. Now you might think day dreaming is a passive experience, not an active one. But that’s only partially true. Day dreams usually begin with a contemplation or a reflection. They usually have a focus. However, instead of rigorously wrestling with whatever we are focusing on, day dreaming involves an active letting go. Letting the mind find it’s own way without being too directive.

I think day dreaming has a bad press. It’s one of the things children are scolded for, and is considered to be sloppy or lazy. I think that completely fails to see the potential in day dreaming. Actively choosing to day dream can bring a whole other dimension to your life. What comes up may well surprise you, bringing you much deeper insights than other exercises can. Solutions to problems can appear in day dreams as “aha!” moments.

So, there’s three kinds of active dreaming to consider and play with this week – lucid dreaming, getting in touch with the foundation dreams of your life, and active day dreaming.